Life is a burning tire

Museum Beelden aan Zee

The Hague/NL

2017

[CABINET]

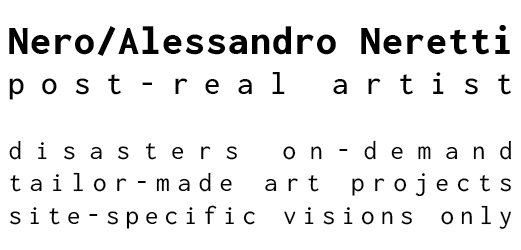

exhibition view | Museum Beelden aan Zee, Cabinet

detail from | sisters, 2017

sisters, 2017 | multilayer pine wood, salvaged aluminium wheel rim, earthenware, concrete, salvaged plastic cloth | 343 x 296 x 77 cm

‘As in an open site, two columns wait for the end of the works. Icons from the past make a comeback and await occupation.’

//////////

Historical note:

The seventeenth-century painter Gerard Houckgeest (1600- 1691) renewed the opinions about perspective in church interiors. For example, he painted a massive diagonal perspective of a white column standing before the tomb of Willem de Zwijger (William the Silent) in the Nieuwe Kerk in Delft (to be seen in the Mauritshuis, The Hague). This 1651 painting influenced Nero in his analysis of this chapel-like exhibition space. With stacked wheel rims, finished off with earthenware columns, these columns share the load of the other supports in this space.

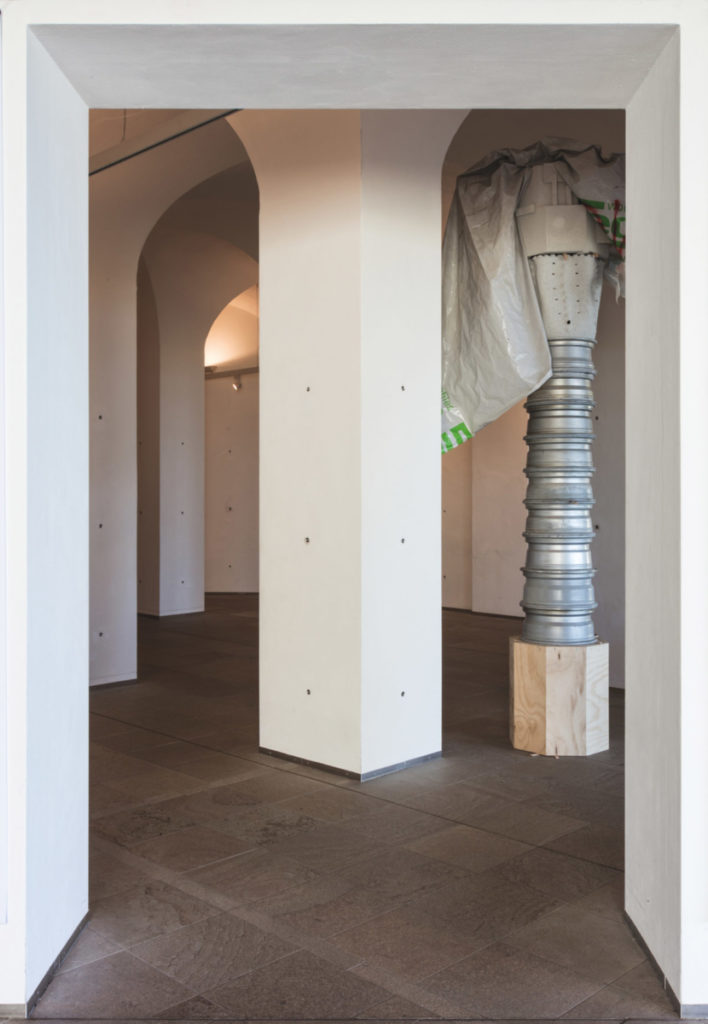

proof of concept (ball breaker), 2017 | salvaged wood, photocopy, mixed media | 186 x 216 x 109 cm

‘After years spent escaping the boredom of the studio, the artist (harassing) brings us his faint memory of an image of a painting.’

//////////

Historical note:

Looking for links between Dutch/Flemish and Italian art, Nero has chosen and translated into contemporary art, among others, the painting Hieronymus in zijn studeervertrek (Saint Jerome in His Study) by Antonello da Messina (ca. 1430-1479), an icon of the Italian Renaissance. This painting shows that Antonello da Messina was the first to introduce in Italy the art of painting and new oil paint technique of his northern contemporaries(Van Eyck, Memling).

This is probably the painting that Antonello brought to Venice to show to his prospective clients as an example of his work.

Here, Nero places the emphasis on the architectural composition and the clear perspective that was seen as novel in the fifteenth century.

interaction with | proof of concept (ball breaker), 2017

detail from | proof of concept (ball breaker), 2017

detail from | proof of concept (ball breaker), 2017

detail from | proof of concept (ball breaker), 2017

lazy susan, lazy susan, lazy susan, lazy susan, lazy susan, 2017 | glazed earthenware, aluminium and plastic ladder, plastic cones, multilayer pine wood, mechanical movement | 157,5 x 229,5 x 92 cm

‘A rotating tray for serving food contaminates a typical sculpture in the Dutch tradition which loses itself in the meanders of contemporary industrialisation; too lazy to disentangle itself, it remains trapped.’

//////////

Lazy Susan is the name of a turntable that is used, in particular, in Asian restaurants. This American invention dates from the early twentieth century.

detail from | lazy susan, lazy susan, lazy susan, lazy susan, lazy susan, 2017

interaction with | chernobyl hills series: easy listening, 2017

(L) chernobyl hills series: pool party, 2017 | alveolar polycarbonate, ink-print on paper, plexiglas, colored paper, aluminium, plastic, museum wall before restauration | 61 x 81 x 13,5 cm

(R) chernobyl hills series: relaxing evening, 2017 | alveolar polycarbonate, ink-print on paper, plexiglas, colored paper, aluminium, plastic, museum wall before restauration | 61 x 81 x 13,5 cm

‘A half-closed window on an imaginary landscape contains a series of layers which blend together two dissimilar landscapes. The static skeleton of the Chernobyl disaster and the luxury villas of Beverly Hills together create a new vision of our time.’

exhibition view | Museum Beelden aan Zee, Cabinet

Lazy Susan, Lazy Susan, Lazy Susan, Lazy Susan, Lazy Susan

Dick van Broekhuizen

Description

A self-made, unpainted wooden box is placed on a folding ladder standing at right angles. The box is crowned with a turntable on which five road cones and five small busts are placed. The cones are vivid orange in colour, and carry a white band. The busts are made of white ceramic material that is coloured with a bright orange low temperature glaze. The box has a metal ventilation grill. Inside the box is an electric motor that drives the turntable. As the turntable rotates, the five identical heads, alternated by the cones, move before our eyes, in endless repetition. Lazy Susan, Lazy Susan, Lazy Susan, Lazy Suzan, Lazy Suzan. Just like a record player, with its needle stuck in the groove.

Turntable

It would seem that a turntable placed on a dinner table is known in English as a Lazy Susan. The waitress is replaced by a device. If you sit at table in a Chinese restaurant in Italy, you can simply turn the turntable to bring your favourite dish before you. This image, strangely surprising and apparently created in an artless manner, possesses a deceptive complexity. In the exhibition Life is a burning tire Nero serves up to us a visual world that is whimsical and serious, childlike and adult. Nero can still draw pleasure from something so simple as a turntable in a restaurant. A turntable in a museum acquires another meaning. Nero’s own version of a Lazy Susan is a criticism of the ‘museum business’, which must constantly serve up favourite dishes to their visiting public. But much of the art we see is the same. You see a work of art, but you must take care, says the orange traffic cone. Don’t you always see, everywhere, in every museum, the same, the same content, the same way of looking at it, don’t you always look at it in the same way? The unusual way in which Nero presents his turntable emphasizes these questions.

Wheel

In the display here in museum Beelden aan Zee the turntable also reminds one of the other areas in the building, in which Nero has used the bicycle wheel and the car tyre as a frame and plinth. A rotating circle has something unending about it, but it also represents dynamics. Travelling, roving, moving, it often takes place by means of wheels on the ground. But a wheel is also an object that you can use as a building block or as an artist’s material, in the way that Nero does. An even more aggressive association: burning tires are often a sign of revolution, of riots that break out, of chaos and anarchy. For Nero they also mean the fuel that feeds the sacred fire, which ultimately dies out. A rotating disc, a record player for sculpture, that alludes to music, but also to deafening repetition, it alludes to dynamics, but also to the danger of endlessly playing the same tune.

Repetitions

Repetition is a well-known phenomenon in sculpture. A sculptural work of art is not as often a unique object as a painting, which always is. Multiple numbers of a painting do not exist: a sculpture that is made in a series is, and this happens frequently. Sculptures can occur in a series of five, or six. Is this an indication of laziness on the part of the sculptor? The identity of the ceramic head is unknown, but Nero has stated that it is a Dutch work. He wants to display a generic Dutch sculpture that is repeated continuously. He is only partly successful in this, because this little figure is not as clichéd as it should be.

Flywheel

The turntable is a sculptor’s tool, and is as old as sculpture itself. After all, in most cases a sculptor has to work ‘in the round’ as it were: a sculpture must be visually interesting from many sides. It is thus handy if you can turn the work round. A turntable, such as is used in the making of ceramic works, uses a flywheel that makes a wet lump of clay turn smoothly in the hands of the potter, so that a vase or other regular shape can be created.

Conclusion

The appearance of this work is closer to bricolage and so-called ‘creative activity’, but after closer consideration it is a pump jack, or nodding donkey. The centrifugal force ensures that all manner of associations are flung into all parts of the museum.

Creation as the only form of resistance to production

Irene Biolchini

On a flight to South Korea, I looked over at my neighbour who was asleep with a vaguely feline-shaped sleeping mask covering her eyes. I think that, should Nero/Alessandro Neretti have been seated in my place, this woman’s face would have ended up on the cover of a catalogue.

These and other trespassings in life fuel the artist’s aesthetics as he has always dealt with an imaginary world where reality seems to lose its boundaries in approaching the ironical and meddled representation that the artist has of the same. It does not involve a sort of surrealism, but rather an accurate selection process in the life experience – with the final objective of creating a coherent line. A methodology in which artistic creation overturns any sort of pre-constituted idea and opposes the idea itself of artistic production that – according to Walter Benjamin – in its ‘productive’ terms adopts the language of the capitalist model without reconsidering it1. One might say that Nero’s art is the furthest from capitalist production, whose system is rejected right from its very core, as testified by systematically adopting discards as stepping stones for his artistic creation. Should we possess the Marxist point-of-view according to which discards are the element on which capitalist economy is founded2, then the action of continuously recycling material according to Nero’s practice is the most systematic action of refusal and reconsideration of the model.

An overthrowing that begins with the artist’s life – and with his way of relating to production environments – even before the work itself. In this blend between art and life every encounter, every fortuitousness, every discard (in aesthetically improved form) may become a part of the work. The words of Manzoni are echoed in this approach, as he admonished: “There is nothing to explain: just be, and live”3. This highlights how every experience, every gesture of the artist can give life to art or how, substantially, there cannot be any distance between one and the other. And it is not by chance that Manzoni himself was the one to create the pedestal for Scultura Vivente, redefining all the characteristics associated with the idea itself of sculpture. A line, namely the one outlined by Manzoni, that resounds in Nero’s exhibition where the remains of a sculptural past are found and disinterred on a beach by the artist himself, dragging the weight of that legacy off the screen and inside exhibition showrooms.

A legacy in which the boundaries between sculpture and painting explode once and for all in the small studio of Antonello da Messina, whose 3D model – completely built with production discards – cohabits with the photocopy of the painting. Colour and the painting of light in Antonello da Messina are set to zero by the low-resolution black and white reproduction; and what remains is the legacy of that imaginary world: the weight and encumbrance of a wooden structure that stands out between the columns. That encumbrance embodies (likewise in the blatant materiality of the rubber column standing upon leonine paws) all the burden of sculpture itself, its being a body, what Vasari refers to as the limit of the sculpture technique in the judgement of painters4. In contrast to the said concreteness, painting invents illusion, depth, manages to abstract and conceptualize.

And here, just like in Vasari, great painted ceramic wheels step in to reconnect the sense of the exhibition, the reinterpretation and reuse of history that escape from post-modern games being so attached (as they are) to life.

1 W. Benjamin, Author as a pruducer in F. Fascina and C. Harrison Modernism: A Critical Anthology, The Open University, London, 1982, 215.

2 K. Marx, Capital. A Critique of Political Economy, Volume I.

3 Original text issued by Galerie Azimut, Milan on 4 January 1960. For the English translation: C. Harrison, P. Wood, Art in Theory 1900-2000. An Anthology of Changing Ideas, 723.

4 Vasari, The Lives of The Artists, lines 31-45.