Who is a good boy?

MAR-Museo d’Arte di Ravenna

Ravenna/IT

2014

[part one]

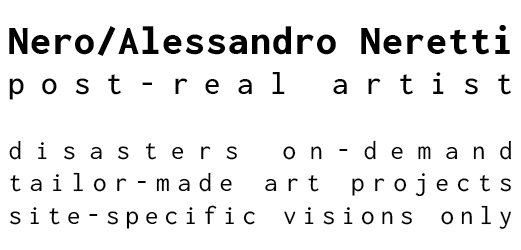

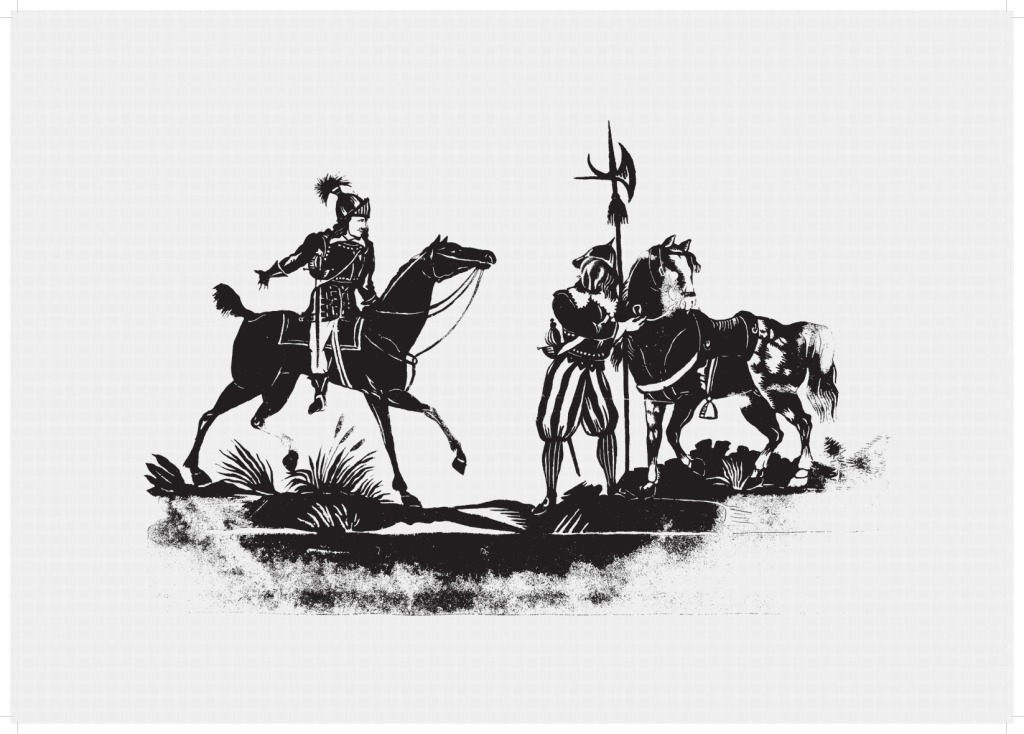

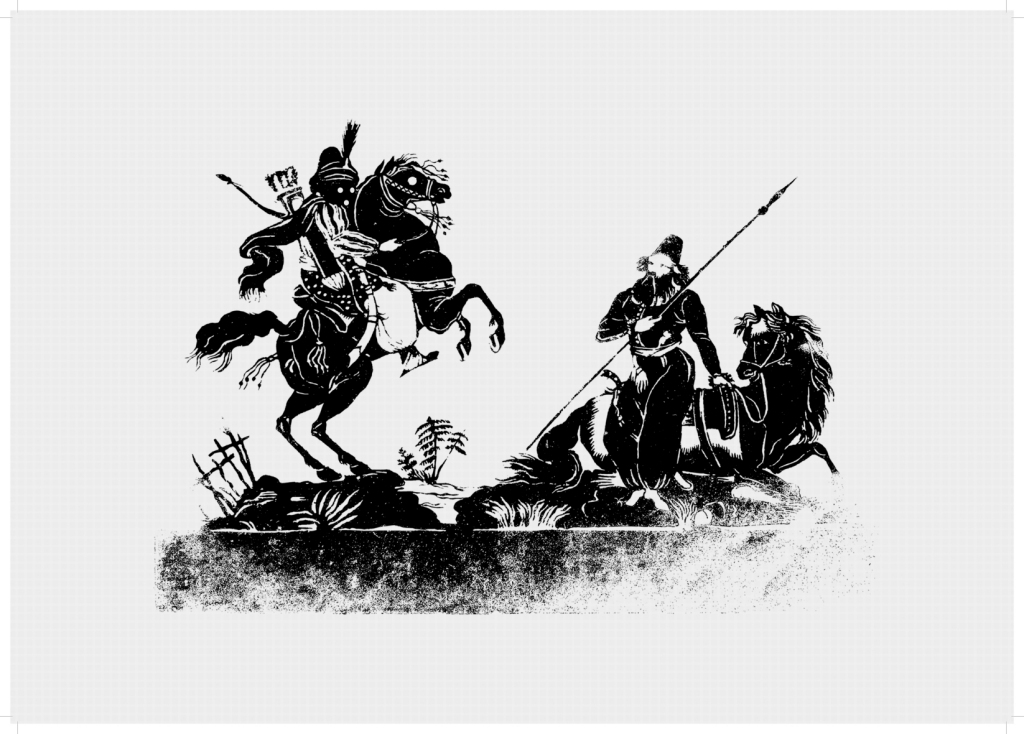

the knights of the sea or my soul hangs out with bad company, 2014 | glazed earthenware, iron, reclaimed wood | cm 310 x 520 x 450

post-real/wrestling series: jake “the snake” robert, 2014 | inkjet print on paper | cm 33 x 48

detail from | the knights of the sea or my soul hangs out with bad company, 2014 | cm 315 x 105 x 92

post-real/wrestling series: el santo, 2014 | inkjet print on paper | cm 33 x 48

detail from | the knights of the sea or my soul hangs out with bad company, 2014 | cm 200 x 178 x 61

detail from | the knights of the sea or my soul hangs out with bad company, 2014 | cm 310 x 105 x 92

post-real/wrestling series: koko b. ware, 2014 | inkjet print on paper | cm 33 x 48

view | post-real/wrestling series

Who is a good boy? That is: who is afraid of the good boy?

Luca Bochicchio

What we are talking about here is art and its justification,

its meaning and its place in our lives and society…

Art is a life and death issue; a human necessity…

Asger Jorn, 1943

Many friends, philosophers and artists of my generation, with a burning passion in their eyes, repeat that they can live their lives no other way, now or in the future. They talk about their “art”, their knowledge and their skills. Nero is one of these.

The first time we talked together at length was while walking together one night. He told me: “Work is everything for me. Anyone who fails to understand and attacks my work does not understand me and is attacking me personally.” I considered the way he identified his life totally with his art as a fatal incarnation of Romantic thought, of the avant-garde and pride of consciousness that was worthy of respect. It combined with a certain inevitable suffering experienced deeply also in his works of art.

It took me time to understand that all Nero’s art, each detail and each stage of development, corresponds to a chapter in his autobiography as fuelled by two sources: the immediate event and a more general poetics, within a system in which many essential keys of interaction with the world clash (allow me to use this term). These keys of interaction determine the methods of procedure and planning for his work: provocation, sabotage, inclusion, contrast, the body, the macabre, the classic and the citation. The inspiration coming from the biographical fact (present and instantaneous) is the artist’s “feeling like a stray” that guides Nero to grasp – or himself make clear – the poetic sense of the road, of wandering through the world. The general poetics to which this daily journey is related is the Christian faith, often resolved in the parable of religious martyrdom and sacrifice as an act of love, freedom and creation. Nero prefers to be defined as a “ceramics tramp” rather than the more elegant term of “art refugee”. You need only walk into his old studio, cluttered with precariously balanced objects, to decode more easily the elements that recur most often in his work, such as a lean-to shelter or the perturbing warning sign: no security exit. A shelter differs from architecture – Nero explains – as it offers the minimum protection of places and objects of “daily consolation”. From an operational point of view, the original graphical representation of Nero’s statement (a pie chart, where each slice illustrates the percentage of: strategic work, architecture of the title, pagan and religious iconography, adverse destiny, communication, and so on and so forth) may be critically labelled as Dadaism, installation, site-specific, photography, procedural and narrative art, performance, critique and social action, sculpture, ceramics, drawing. Am I exaggerating? Not at all. All these languages are held together by a unified poetic vision in progress, and a knowledge of the means and creative tools determined by (hard and constant) work, by the search for truth and self-improvement.

In his current phase of artistic growth, Nero has begun to re-orientate himself within his poetic alter egos, with the unconfessed fear of stopping or repeating himself. In fact, in this exhibition at the MAR in Ravenna his procedural and conceptual awareness explode powerfully. The work clearly demonstrates the artist’s ability to animate and display mythical images and read space, but above all his wilfully shocking desire to square up to the Museum, which Nero sees as the classical Institution of knowledge, an ambiguous place where heroes and saints are consecrated, housing cathartic and apotropaic images and materials.

In the conceptual and material creation of his work, Nero pushes his research to the limit of plastic form; at the same time, the artist implements a behaviour that seeks to push back the accepted social customs in order to undermine the decision-making pyramid that governs us. In the museum, Nero is like the lunatic who became king for a day in mediaeval carnival times, a disturbing element that tells you what you do not want to know and may not say. Indeed, even when collaborating with MAR his critical process of going beyond the bounds started immediately, indeed well before the inauguration of the exhibition. With well-oiled logical method, Nero immediately proposed an “unscheduled” extra to the Museum curators by requesting additional space beyond that set aside for his works. He wanted to know who could make decisions regarding his work, and on what basis. Finally, he attempted to involve private industry in implementing a change in the arrangement of the allotted space. The failure of this attempt fuelled the consciousness of the creative process, created ad hoc, with works sometimes set between classical pedestals taken from the MAR storerooms. Nero partly alters their essence, contrasting them with other anti-classical and anti-rhetorical supporting structures, each made by hand.

My reading (from a broader and a museological point of view) is Nero’s desire to elevate above the spectators his Cavalli – Horses and Cavalieri – Horsemen, these merciless announcers of the Apocalypse to the heirs (us) of Eurocentric and Christian hegemony. The air-rending shout of the soldier should be the last call to arms against barbarism. The images of the horsemen, on the other hand, do not convey strength and calm, but rather they disappoint us and move us, perhaps amusing us by their tragi-comic desire for mythological revenge. The deformed condottiero that urges forward his limbless horse is so awkward that he is choked by his own iconographic symbols (wings and snake). The screaming warrior is merely a genetic mutation of the Greek soldier, a contemporary upgrade of François Rude’s La Marseillaise (1833-36): a glazed scrap of history, as black as sin.

Christian and Pagan, then, Neretti develops in a complex but uncomplicated way the loss of identity as well as political and economic power, but also the values of sacrifice and trust in God. And he does so using the technique and tradition of ceramics, which he knows so well.

In the Christ Child with stigma, the monkey embodies the Child Jesus not as a provocation, but expressing the desire to affirm the continuity and sacred evolution of life on earth, from a polycentric viewpoint rather than that of the humanistic and Christian philosophy. By using gold in the stigmata, Nero shows the splendour of life enclosed within sacrifice and love. This single image, just like medieval iconography, adds new layers and intensity of meaning. The titles back up the symbolism of works such as Preventive war is an ugly ugly dog, or the disturbing State-Mafia Negotiations, where power is identified in the one among the gnomes that has no mouth to speak but the third eye in his brain and the ears of Silenus. In Nero’s mythological version the satyr, who in Greek tradition knows the truth, uses his knowledge for evil ends. Another myth tells how King Midas (who possessed the power to turn matter into gold) grew donkey ears after believing the truth conveyed by Silenus. In these works, Neretti’s lean-to shelter reappears in the form of discoloured and robust planks from the work-site: the precarious structure of the world economy … and his personal balance. These structures are bulky and unsightly but in their poverty they provide a link between sculpture (the contemporary idol) and the classical plinth, in fact turning everything into a work of art – environment and spectators included.